Distances, Engines, and Speeds

Alex Anderson 🚀, September 23, 2020

Alex Anderson 🚀, September 23, 2020

Design is all about making decisions and understanding the consequences of those decisions. Things like “What color should this button be so the user knows they can click on it?” or “How long should this transition last to be delightful but not distracting?” or “How often should we pop up an ad to maximize engagement?”

When designing a game like Thorium, these kinds of decisions make or break the experience. I have in my mind a number of goals and principles that I want to incorporate. Things like

- We will use accurate sizes and distances for everything on the starmap.

- The universe should be big enough that it would take weeks to visit everything. That maintains the feeling of vastness and keeps the crew from calling for help at any sign of trouble.

- Warp Engines (faster-than-light travel) shouldn’t be used as a crutch to easily get out of dangerous situations. It should be risky to use Warp Engines while in a battle.

- There should be a non-trivial amount of travel time - say at least 5 minutes - between destinations so the crew has time to plan, prepare, decompress, and manage their ship systems.

That last point is crucial. If the travel time is too long, crews will get bored and become disinterested. If it’s too short, they won’t have time to do important stuff in-between the moments of action.

Navigation

Choosing where to go is the simplest part of this whole process. The Navigation officer will have access to the entire starmap catalog. They’ll be able to see their ship’s position in space, measure the distance between stars, search for specific stars and planets, set waypoints, and choose a star to set course to.

Once they’ve chosen a destination they want to go to, the Pilot can use thrusters to point the ship at the desired destination, with help from a guide on the Main Viewscreen. At that point, the Navigation officer can ‘Lock in’ the course, which would deactivate thrusters until the crew reaches their destination, so as to avoid accidental maneuvers that would put the ship off course..

Distance

After creating a preliminary starmap, I found that there are a lot of stars in close proximity to Earth that can serve as good destinations for missions. I also found that most of the stars we have cataloged are within 1000 light years of Earth, so adding any stars beyond that radius would just be me making stuff up. That gave me a rough distance - the starmap will be limited to a radius of 1000 light years.

Distance is only one part of the equation. We also need to know how long it should take to get places and the speed that we’re traveling. If we have two of those three parts, we can complete the equation. So let’s take a look at speed using some known values.

Travel Time

The distance from Earth to the closest star, Alpha Centauri, is 4.3 light years; Procyon is 11.4 light years from Earth. Travel to either of these stars at cruising speed should be between 1 and 5 minutes. That means we’re looking at somewhere between 420,000c and 5,000,000c (c being the speed of light). Let’s pick a nice round number: 2,000,000c

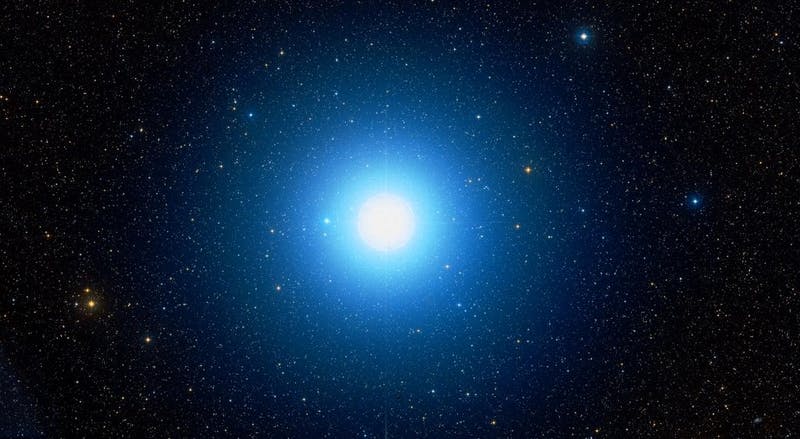

Procyon, one of the closer stars to Earth

Extrapolating that to the diameter of the entire starmap, at 2,000,000c, it would take 8 hours 45 minutes to go from one end of the starmap to the other. I think that’s a good number, since it means over the course of several missions, you could find yourself just about anywhere in the starmap, but it still takes a long time to get anywhere in a single 1 - 2 hour mission, especially since you don’t usually spend the entire mission traveling.

Obviously, this is an absurdly fast speed that isn’t reasonable in other contexts. For example, at this speed it would take 18 days to cross the entire Milky Way, and just over a year to get to Andromeda, the next galaxy over. And that’s at cruising speed.

Still, this speed fits in with my desires for the narrative, and discrepancies in why humanity doesn’t colonize more worlds faster can be explained in other ways. For example, perhaps fuel runs out quickly and can’t be synthesized easily on a spacecraft. Or the engines overheat during long-distance travel, requiring large amounts of coolant or regular rest stops.

Planetary System Travel

The distances within a planetary system are significantly smaller than those out in interstellar space, but still big enough that FTL is necessary. The ship will still have Impulse Engines (tentative cruising speed: 1500 km/s) for maneuvering at sub-FTL speeds, but getting between planets will require Warp Engines. However, our speed of 2,000,000c is way too fast. It would take less than the blink of an eye for a ship to get from Earth to Neptune. Because of that, Warp Engines will automatically go slower in planetary systems. Think of it as a no-wake zone on a lake. We can say that the gravity or solar winds from the star makes high warp speeds prohibitively inefficient.

Within a planetary system, a reasonable cruising speed is 100c. This takes about 2 minutes to get from Earth to Neptune. Why do we care how long it takes to get to Neptune? In order to go faster to cover interstellar distances, we have to escape the planetary system.

That means a routine trip from Earth to a planet in the Alpha Centauri system would take about 6 minutes: 2 minutes to leave the Sol system, 90 seconds to cross interstellar space, and another 2 minutes of system travel to get to the planet.

That’s still really fast for some circumstances of solar system travel. Traveling from Earth to Mars, which is prohibitively far for Impulse Engines, would take less than 3 seconds at cruising Warp speed - way too fast to be able to properly slow down in time. Because of this, there will be a minimum Warp speed - defined as 1 / 100 of cruising speed - and a series of Warp factors between the two which grow linearly (Star Trek does exponential Warp factors, but I find it a little complicated). I think 5 is a nice number, so that’s what Thorium Nova will ship with. With that scale, at Warp 1 it would take 3 minutes, 45 seconds to get from Earth to Mars, a reasonable time frame; even Warp 4 would take 45 seconds, which is long enough to be able to slow down in time. This won’t apply so much at interstellar speeds, since it would take 1.75 hours to get to Alpha Centuari at Warp 1. Still, the option is there.

There will also be two steps above cruising speed, called Emergency Warp and Destructive Warp. These are used only in emergencies, or when plotting an intercept course with a ship traveling at high warp speeds. The heat generation and energy consumption for Emergency and Destructive Warp are exponentially higher than Cruising speed to discourage their use. Conversely, going at speeds lower than Cruising speed requires significantly less power and generates less heat.

Jumping to Warp

In any circumstance, whether in interstellar space or within a system, the ship cannot just jump to Warp. This is to discourage flippantly activating the Warp Engines or always running away from a fight.

In-universe, Warp Engines require a bit of a jump start to actually get going. Think of it like the Flux Capacitor in Back to the Future - Warp Engines only activate when supplied an instant supply of 1.21 Jigawatts.

It’s the ship that made the Kessel Run in less than twelve parsecs!

This power comes from a real-world power storage mechanism called a Compensated Pulsed Alternator, but “Alternator” sounds too automotive. Let’s call it the Compensated Pulsed Dynamo. This is essentially a giant flywheel that can be spun up to incredible speeds over a long period of time. When engaged, the rotation energy is immediately converted into power which feeds directly into the Warp Engines, giving them the juice they need to get started. (Intrepid and foolhardy crews might figure out how to reroute power from the Dynamo, allowing them to supercharge other systems). Powering up the Dynamo will be referred to as “spooling”.

Spooling the Warp Dynamo should take at least 30 seconds - not too long that it’s frustrating, but long enough that it’s not something that you do on a whim. That’s only to get to Warp 1. Spooling to each additional warp speed should take less than 5 seconds, and can be done while at Warp speed. The Helm officer can either choose to spool all the way to the desired speed while at full stop, or continuously spool and accelerate while traveling at Warp speed.

Spooling the Dynamo will require a lot of power, which puts a strain on the rest of the ship’s power system, and heats up the Warp Engines more than just traveling at warp speed. This is to discourage keeping the Dynamo spooled all the time. Also, Warp Engines can only be activated while at full stop, with the Impulse Engines deactivated. If the ship is under attack, this makes them sitting ducks, and further encourages them to defend themselves instead of run away.

Impulse Engine Travel

Impulse Engines will be reserved for flying around planets and mingling with other ships. I want using Impulse Engines to feel much more like a cockpit simulator, like Elite: Dangerous. Acceleration will be a function of the mass of the ship and the thrust which the engines apply. Heavier ship - slower acceleration. Cruising speed will be roughly the same across ships, though.

Above, I mentioned the cruising speed will be 1500 km/s. That’s really dang fast, way faster than anything else Humans have ever created. For reference, the Parker Solar probe is being whipped around by the Sun’s gravity, and is only going a paltry 95 km/s.

The reason I chose 1500 km/s is because it would take about 5 minutes to get from Earth to the Moon at that speed. Any Warp speed is way too fast, and I want travel around planets to be smooth and uninterrupted.

It’s possible that I might limit the Impulse cruising speed to a more reasonable 300 km/s and have a “boost” which makes the ship go faster than 1500 km/s. I haven’t thought through this much, if you have any ideas, let me know!